I’m writing this in response to comments made over the years about friendships I’ve maintained with persons who are diametrically opposed to many of my core values. Most of these comments have the tone of disapproval, others just sound flummoxed with me.

Let me say from the start that my reason is not conversion. Such an ulterior motive would make such a friendship one of utility, not a true friendship, to use Aristotle’s hierarchy of friendship. In the Book VII of his Nicomachean Ethics, he distinguishes between friends who are bonded by shared pleasure, the lowest; those who find each other useful; and true friends who share a common vision of life.

I’m sure the diligent reader just noted that I created a huge hurdle for myself to jump, namely, how can I be friends with those, who I said above, do not share my “core values”? Doesn’t this constitute an impossibility according to Aristotle’s criteria?

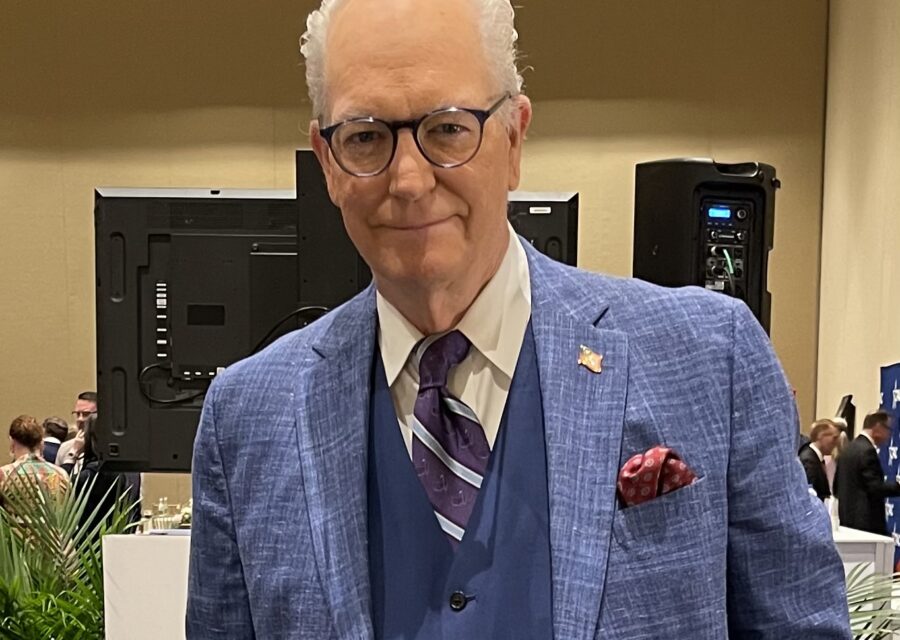

Since I regard myself as someone whose mind and heart has been shaped by the tradition from Aristotle and St. Thomas Aquinas to Jacques Maritain and Etienne Gilson, I take this challenge seriously. In order to answer it, I have been made to reflect upon those specific friendships, both past and present, to find, if I could, what “common vision” we may have shared.

What came immediately to mind was the acceptance and respect I shared, and still share, with these persons. Several of them, in addition to being liberal Democrats, have been homosexual, which I thought important to mention, though I didn’t want to put it in the headline.

Such was the case of my friendship — call him “W” — of over 40 years with a man whose eulogy I delivered only a few years ago. We shared a love of Flannery O’Connor, who had been a personal friend of his, as well all things literary and musical. I spent hours at his piano singing show tunes while he thundered away, magnificently. I still miss him.

When issues of faith, sexuality, or politics came up, our conversations were always direct but civil and punctuated with great guffaws of laughter, usually provoked by his puncturing of my inflated ego. But W never hinted at any disapproval of my conversion to Catholicism at age 34 — he also loved the convert, Evelyn Waugh — or the help I offered to George W. Bush — a man he didn’t love — in his campaigns and years in the White House.

Unlike many liberals nowadays, W did not look upon me as a moral inferior for being conservative, Catholic, or Republican. He did not assume I was a racist or felt disdain toward the poor. Oh, W would correct me sharply if I said or did something out of line, but I accepted the rebuke as a lesson given by a man whose judgment I respected and whose love I trusted.

What I have said of W can be applied to all my friendships with “liberals, Democrats, and pro-aborts.” There is, in fact, a “common vision” that stands behind the differences about politics, religion, and morality, and at the heart of the vision is acceptance, respect, and love, the truest love of willing the good for the other.

Another dimension to that common vision is a sharing of the greatness of the world and its culture — music, poetry, fiction, film, ideas, history, travel, and mutual friends. After all friends do not simply sit and stare at each other, quite the opposite, they look out at the world together and share in its delights.

At this point the reader might be thinking that I have ignored the looming question of how I could share a “common vision” with, say, a pro-abort. My answer is to say that not all who support abortion do so with the virulence of a pro-abortion activist. Not all who call themselves feminists despise conservative men who smoke cigars and play golf. Those friends of mine who are abortion supporters respect my view and those of other pro-lifers. They agree to disagree, but do so in way not to dismiss the subject from conversation but to admit their minds are still open on the subject.

The same can be said of liberals and Democrats: few of them are as unpleasant as the liberals on TV and radio who cannot address any difference of opinion without a mocking, scornful tone of voice. I cannot share a common vision with anyone, on the right or the left, who treats others with instant disrespect because of a label, whether of their party affiliation, religious belief, sexual orientation, or taste in music.

At the heart of liberal scorn is the belief that “all the rest of us” are their moral inferiors, which makes friendship impossible. I fear that conservatives are developing the same attitude toward liberals — that they hold a monopoly on the moral high ground. This may be the main reason I have felt less at home lately in what’s left of the conservative movement.

The gradual politicization of American culture since the resignation of President Nixon in 1974 — driven by the endless victory laps of the media — has made “across the aisle” friendships less and less likely, especially in the area I live around Washington, DC.

And since it has become a habit “to google” a person after you meet him or her, before pursuing further contact, many possible friendships never get off the ground. That person you found delightful at a concert, or a bookstore, a party, at church, or standing in line at the grocery store turns out to a wretched “Republican” or “Democrat,” or whatever label makes him or her an “untouchable.”

Friendship faces a difficult future, I fear. It’s for this reason I offer this explanation of what has appeared to some a disconnect between who I am and who I call “my friend.” Perhaps the “common vision” that grounds a friendship is larger, and more nuanced, than we think.

May I say something briefly about your admiration for Flannery O’Connor? Her short story Revelation sums up her vision of life, and that story reveals a liberal and an ardent follower of Teilhard de Chardin. Modernism, not Thomism, drips from the pages of her work. I have two essays on the subject on my blog, one on her non-fiction writing and one on Revelation; I invite you to read and criticize them (just google ‘O’Connor’ and ‘White Lily Blog’).

You have been hustled about Flannery O’Connor by her astute handlers. And it is possible that the same is true for some of your friendships here. “Delightful” is not a sound basis for judgement, as many otherwise unsavory persons may be described that way. Sometimes Satan comes as a man of peace, as Bob Dylan says in that wonderful song. Many a pimp has appeared to be so, and it’s good to be forewarned of it by the internet. Honestly, if you are friends with any active pro-abortion person, are you sure you aren’t thereby avoiding the war with secularism? That you aren’t repelled by them because some part of you ‘understands’ their position?

I say that because in the secular state, with its sex socialism, with its two liberal parties and no other alternative for voters, both abortion and welfare are merciful, truly merciful, alternatives to the poor, and the democratic party merely serves as a dispenser of the unspeakable. We are caught, in the secular state, pinned as in chess to equally distasteful alternatives, for the republican policies do not result in economic soundness and in fact churn out poor. Let me refer to your comment about ‘conservatives’–it’s possible that it’s not their attitude so much as the error of their solutions you find objectionable. I know my associates at church (traditional mass, of course) drive me away with the garbage they pick up on the internet and radio, the casual racism, their opinions about women, so unCatholic, so unconservative. The only solution to our economic sickness (I say in relation to the two alternatives, the two liberal parties, between which we are presently nailed) is a return to the Catholic state, and that would require evangelization and a clear platform. Hungary built FIDESZ and so could we build a truly conservative party that would restore those conditions that make abortion such an attractive alternative to the poor, hopeless, unmarriageable women who presently turn to it. If you have done any work in this area, you know simply convincing a woman not to kill her unborn child is bittersweet, for often she will return to the conditions of concubinage or promiscuity because of economic realities that we cannot address under the present utterly predatory economic regime. We need a better world for her, and we are not actively seeking it because we know instinctively that this one cannot be reformed. It is protestant and it is flawed.

I argue this in a novel called Run, you can find it at Malapert Press at wordpress. Catholics on the first space colony, equipped with the technology, make a run for a remote, terraformable asteroid and set up both a Catholic state and a monarchy. I argue, through characters and action, that the old feudal economy, so local, based on widely distributed ownership rather than income, will come into its own in space. I’ve probably really lost your attention now! But the characters argue well!

In any case, do you grasp that the long slide down of secularism has now reached the point where we Catholics are illegal? We may not teach our beliefs now (unless we adjust them, as the Synod attempts), and you may not say to your homosexual friend, repent, reform, return to the Faith. It is you who are unsavory now.

As many things are sinful, we are to love the sinner and that’s what the message is. I don’t like the way many things are going, but my nine year old can tell you that we can rebuke wrong behavior and still love the person. Alas, Jesus supped with prostitutes, tax cheats………ALL. Your verbose diatribe above is nonsense.

Deal Hudson’s commentary is especially welcome at this time, because he implicitly affirms two valuable concepts that seem to have fallen by the wayside: 1) humility, and 2) uncertainty. The chain of thinking that goes, “I am right; therefore, if you don’t agree, then you are wrong. Because I am right, I am entitled to condemn those who disagree, and to do everything in my power to enable our social and political structures to coerce those who disagree to conform to my vision of rectitude.” The arrogance of this attitude is quintessentially un-Christian and undermines and gives the lie to any pretense of respect for the values–and value–of others. This is well exemplified by Ms. Baker’s comments above.

Wow, it’s rough out there. I’m pretty sure I know W, also. I was in one of his classes over 50 years ago. His influence is still strong.

I haven’t been here in awhile but I had to take a moment to comment on this piece; I believe that the Lord’s commandment to Love was not meant to be played out in the comfort of our Church Communities (although personally I would like to one day experience in my Catholic Parish). We learn that in the scriptures how it breaks God’s heart to lose even one soul. If that is the case, then wouldn’t that require friendships like the ones Deal describes here. Of course there is a risk that one might falter along the way amidst such persuasive and brilliant minds – but if the motive is to bring the presence of Christ, will not Grace abound in the end? I think that it speaks of the childish level of Faith our Catholics have been “kept” and not only Catholics over the last 20 – 30 years. If our Faith and Morals cannot hold up to anyone or anything opposed – what good is it?

I just watched the movie “The Inn at the 6th Happiness” and I learned so much about how our example of love and friendship allows God to move the hearts and souls of others; perhaps more than a good debate.

Thank you for challenging us Deal – I found this piece provocative and instructive.

“while we were yet sinners, Christ died for us”

God loves us all in spite of our weaknesses and we should ,as Christians, reflect this Christ like love to all people everywhere.

Thank you Deal for the time and effort you put into this well-written article. Much of what you wrote I can relate with because of similar relationships in my life. I do however have some differences in The way I see relationships with liberals, homosexuals, and Democrats. Because I love them I must share the truth with them. Love demands that I attempt to win them over to the truth, how else will they ever be free from the chains? If I don’t warn my friends that I love, Am I not just holding their hand on their way to hell. There is always a temptation for the more diplomatic among us to flirt with moral relativism for the sake of relationships. This desire I believe comes from a love for men more than a love for God Himself. Being a manifestation of God’s grace and truth with my liberal friends has proven occasionally to instill the fear of God in them. This brings so much joy to me! We all know the Hymn!

It was grace that taught our heart to fear and Grace our fears relieved”

Thank you for the article, I love your winsome heart and your commitment to draw people together.

I feel like I missed the part where you explain how you can be friends with them, unless the answer is “because the specific ones I’m friends with aren’t so bad”

I was hoping to glean some advice here on how to maintain friendships with people I want to like, but despise because of their views, which they didn’t used to hold.

Hmmmm, I think I need to do a follow-up. Thanks for your question. Deal

People are not changed by rejection or demanding that they agree with one’s own faith or philosophical outlook on life. I have found that my wide range of friends do listen to me if they believe that I have a deep respect for their humanity. We also share values. I have a friend who is very new age, yet her faith in God puts me to shame. She knows of my faith, my commitment to follow Christ Jesus, and she respects that.

We all plant seeds, by our actions, as well as our speech. To reject someone because they disagree with plants a seed that will only bear bad fruit.

I have been lambasted for my faith b people who really have no idea what I believe. So why would I want to put another through that? I seek to treat others as I want to be treated…..yes I fail….but keep trying.

Good article Deal, thanks for sharing.

Peace

Br. Mark